Disclaimer: this chapter is translated by DeepL and edited by non-native speaker. The text will be updated after the translation has been corrected by a professional editor.

Returning to the matter of the 95% that died and the 5% that survived, clearly, the issue is not so much the aphids as the principle. Imagine how companions in the human world would react to the news that 95% or more of their loved ones and good friends were about to perish in the worst possible sense of the word. And they would only have themselves to blame for the sole reason that they are traitors, or striking individualists, as they would refer to themselves. These are people with no desire to synchronize with others for the sake of natural human needs or even a natural lifestyle. To them, what is natural in the world of nature means nothing, and conversely, all that is unnatural they hold as meaningful and dear. To put it bluntly, they are degenerates. That is what they are, harsh as it may sound.

Those companions who are capable of saving themselves by evolving into a new species look around at all the degenerate types and think erroneously that their comrades may be saved, too. If you could just help them understand a little more about how life really works… But explanations take time and energy. And for the comrade willing to take it upon themself to do the elaborating, the transition to a new species, which is after all a collective mutation, is put on hold. The next thing you know, it has been cancelled altogether and everyone dies out. From a paleontological point of reference, they become extinct, just like the mammoths. That said, only those who were already dead in life will die out in the paleontological sense of the word. The difficulty of spotting those among us who are already dead and yet who continue to move around, eat and procreate comes down to what they call an optical illusion.

Here too we discover that a balanced life philosophy is a factor for survival. Theoretically speaking, if “comrades” were able to make a timely distinction between the living and the “dead,” i.e. those who are alive in the paleontological sense of the word from those who will never return to a natural order and will inevitably die out as a species, there would be no hindrance a new collective mutation.

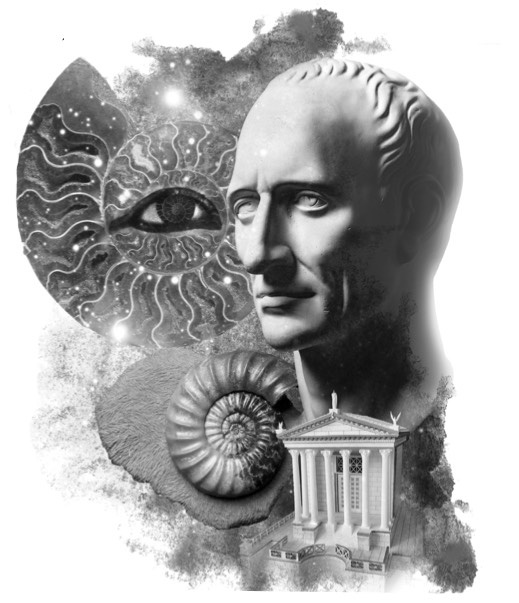

Contemplating a fossil community, more precisely the bone-bearing layers in sedimentary rocks or layers filled with invertebrate remains, an activity in which Octavian Augustus is known to have been engaged, prompts a person to entertain certain thoughts. This is the great value of paleontological outcrops.

It would be best to pay no attention to “living corpses” at all, and as such to avoid wasting time and energy on them. And yet unless you have understand the phenomenon of “the dead” in sufficient depth, distancing yourself from them will be not only difficult but nigh-on impossible.

“Living corpses” have one particularly irksome trait — they want to feel important. On some subconscious level, they know that they have condemned themselves to extinction, and this fact causes them to feel that they are nothing. They long to rid themselves of the emptiness they feel, but instead of coming to an acknowledgement of their worth naturally by ridding themselves of painful perverse addictions, they construct a dark fulfilling emotion by sucking energy from others. Especially, they take to dumping on their neighbour embodying the principle of the Two-Faced Janus, finding ways to intrude into the lives of others. Such types will find a way to deceive you, and when they do, you will become material for their manipulative games. In other periods of history, this type were referred to as vermin. Here we choose to use to term ‘living corpses,’ those all around us suffering from a sense of nothingness. For ‘living corpses’ it is about the final reckoning; for everyone else, it’s a matter of discernment..

It is clear that this initial idea of distinguishing what we refer to in a specific sense as “the living” from that which we refer to in an equally specific sense as “the dead” has numerous implications. The idea goes beyond tsarist knowledge and touches into the realms of the imperial. It is no coincidence that Octavian Augustus, the greatest emperor of the Roman Empire, transformed his palace into a museum of paleontology. The palace museum however was no simple analogy of the modern day equivalent. Today, museums of paleontology are designed by people who embody the standard worldview, and everyday mode of thinking that is a far throw from imperial thought. The most fascinating part of our discussion on sacred paleontology begins here with the inferences that are to be drawn from this initial idea surrounding “the living” and “the dead”.

Did you enjoy this chapter? Read the next one. The riddle of the god Amon and the ammonites

Donations from patrons will be used to translate the book “Sacred Paleontology” from Russian into English. Meniailov has already written more than 50 chapters.

One page of the final professional translation costs us 35 USD. We accept crypto and fiat.

To be continued …